I mostri (Dino Risi, 1963)

Taken From Life (Attori non si nasce. Formazione, scuole, casting per i media italiani - November 2-3, 2023)

A cura di Silvia Vacirca.

In Italy, the institutionalization of the practice of film and television casting direction is a recent phenomenon in the entertainment industry. The Sapienza research unit had the goal to study that process of institutionalization in order to understand its role in the shaping of the new media industry, using the methodological tools of production, cultural & media studies. The “choice” of an actor for a film or a TV series - apparently a “natural” process based on intuitive thinking – is in fact the result of a complex and delicate business involving a network of agents and interests where psychological, bodily, cultural, social, economic, and artistic issues intersect. Of course, the “choice” of a determinate actor to play a fictional character strongly contribute to create the character. In this regard, the Italian costume designer Piero Tosi kept repeating that “cinema is made of faces.”

A casting director has to match the perceived qualities of the actor with the perceived qualities of the fictional character; but it is also true that the character is a generator of acting qualities. It can be argued that casting directors professionally conduct what we all do when we make sense of the people and even the things around us. According to Amy Cook in Building Character. The Art and Science of Casting, observing actors take on roles on screen improves our ability to “interpret” those roles in our daily lives. The study of casting in the cinematographic field has therefore unexpected but important implications in the field of the democratic practice, where we are witnessing the development of what the historian Emilio Gentile has called a “democrazia recitativa.”

My report is the result, in synthesis, of a one-year period of research that I conducted at Sapienza University of Rome on F-ACTOR Forme dell’attorialità mediale contemporanea. Formazione, professionalizzazione, discorsi sociali in Italia (2000-2020) (‘Forms of Contemporary Media Acting. Formation, Professionalization, Social Discourses in Italy 2000-2020’) which focused on casting directors and casting practices for film and television. My research has produced results – for which an empirical sociological study based on a much larger sample would be necessary – that highlight some possible lines of research regarding the relationship between casting practices, the entertainment industry and the acting profession in Italy:

- how the new media landscape has influenced casting practices;

- the specificity of the Italian case regarding the role of “acting” and actors;

- the role of casting in fabricating perceptions of nationality, society, class and gender, tackling diversity issues in Italian content production and the media industry in general.

My research encountered a lot less difficulties in contacting casting directors – that I consider an integral part of my research results – compared to young actors (whom I interviewed last year); a result of the need for legitimization felt by the casting director’s category, which during my research was lobbying to foster a view of their work as worth of artistic recognition in the context of the prestigious David di Donatello competition. A battle which they have recently won.

The advent of digital platforms in Italy and the consequent intensification of the demand for content has led to a greater demand for actors to be cast in serial products aimed at "teen" audiences. As confirmed by a casting director who spoke with me during my research, Italian demand for serial content increased in the last two decades, leading to a greater demand for young actors. These actors, according to her, inevitably must be taken "from the street," according to a practice that the film and television industry define as "street casting." The practice, which in recent years has also spread to the fashion industry, consists of a search for “fresh” faces, not necessarily with a professional background and not belonging to the entertainment field, in order to satisfy specific creative needs.

The role of casting online platforms, such as Spotlight in the UK, which specify the actor’s physical type and his skills is now relevant. The most common alternative method of recruiting is the "self-tape," an audition mediated by a screen, usually a phone screen, that actors must organize independently. The practice of the "self-tape" increased due to the national pandemic lockdown and became institutionalized due to its cheapness and versatility. Actors, especially non-professionals, understandably despise the “self-tape” because, according to them, it deprives them of the “magic” that comes with meeting the director in person. Some actors mention their physical presence and face, not so much their ability to act or improvisational skills as decisive in the audition process. In the practice of the “self-tape,” since it is script-based, it becomes relevant the self-directing actors’ ability.

However, the “self-tape” has not replaced the live audition, but instead it carries out the function of skimming and widening the performers’ potential pool. In-person auditions are carried out only in the final selection phase together with the director. On the one hand, the “self-tape” has the merit of allowing work to continue even during pandemic or other catastrophic lockdowns, on the other hand it broadens the range of experimentation: given the same amount of time, there is the possibility of viewing a lot more actors than in presence. Furthermore, it allows to bridge geographical distances that would make it impossible, in some cases, to carry out an audition (I called this the “democratizing effect”). On the other hand, a few casting directors say it has the limit of being a poor tool since the actor does not have the possibility of engaging with and “adjusting the shot” together with the casting director, as it would happen with in-person auditions. Though the Italian version of this phenomenon lags behind the American one, it has favored the emergence of a new specialized professional figure in the Italian scene, who is predominantly female: the casting director. The career’s paths of Italian casting directors’ are various. They often come from the role of assistant director but also from theater and advertising direction.

Although, at first glance, the greater demand of young actors for "teen" products forces the Italian film and television industry to street-cast their performers, in light of the results of my research, it does not seem entirely satisfactory as an explanation for the adoption of "street-casting." In fact, the length, cost and laboriousness of "street-casting" does not justify a practice that, from a production point of view, is very expensive, as the case of Piranhas (Claudio Giovannesi, 2019) highlights. In my opinion, it would perhaps be more appropriate to consider this practice as part of a particular aesthetic, a mode of production, a film culture. It is ultimately a film culture that deserves to be explored.

For example, the practice of street-casting means that many young actors are selected without considering previous theatrical and acting experience. According to one casting director I interviewed, this is normal because “at their age one cannot already be an ‘actor’." This is an explanation that is plausible, but only as long as one does not consider at least the possibility that productions could choose to cast young academy-graduated actors to play "young teenagers" instead. According to a young Afro-Italian actor I interviewed last year, this would force the productions to pay the professional actor more. According to the same actor, it would be for this reason that the Italian industry has no interest in favoring the advent of a star system that would raise the so-called "above the line" costs.

Auditions for actors “taken from the street” are organized when it is necessary to look for particular human typologies, perhaps with specific skills. For example, when a production is looking for the role of a sportswoman, and this practically always happens when looking for children. Some art house films have as their starting point “not to use seasoned actors but rather people taken from the street because directors are looking for faces and truths with an access to the purest realism.” In general, the suitability of an actor for a “character” concerns its physical appearance and the ability to convey the movements, intentions and emotions of the “vision” the author has in mind.

As regards the job description of the casting director, from a technical point of view, it seems to consist of examining the script, with a list and characteristics of the characters to be compared with the vision and desires of the director. At this point the research begins by drawing up a cast list to be sent to the actors’ representation agencies to receive their proposals that also take into account the conditions necessary for filming: period of availability and, if necessary, place of residence of the actors. Once the proposals have been received, integrated with a cd’s own ideas, he proceeds to request self-tapes and/or organize live auditions. Once the video material has been acquired, it is organized, a selection is made and it is shown to the director who will evaluate it. Once the shortlist of choices has been identified, the casting director puts the agencies and production in contact to finalize the agreement. The creativity of the casting director seems to lie in intuition combined with the ability to understand the characters of the story and to be in tune with the director’s vision. Previous experience and the search for “fresh” faces are the ever-evolving archive from which a casting director’s intuition “fishes for.”

In the interviews I conducted with casting directors and auteurs, a difference emerged between auteur cinema and commercial cinema, but the most macroscopic difference seems to be between an auteur film made for cinema and a film or series made for television. The term “commercial” from the point of view of the cast can be considered relative to the attention mainly paid to the quantity of public that such an actress or actor is believed to attract. The aim is for high revenues and methods of expression and content that are imagined to be appreciated by the greatest number of people. In casting, the focus is on actors known to the general public.

When interviewed on the issue of gender gap in the film and television casting, some casting directors pointed out that more than the quantity of male or female roles, it is the restricted age-range of the main roles intended for women that counts and is appalling: “When there are important female roles they are mostly for young or very young women and naturally beautiful ones.” In this context, it is important to underline that the final choice of cast is always made by the director.

On the other side, the auteurs I interviewed underlined their lack of practice and knowledge of this new figure of the casting director and a certain impatience about it. In fact, what emerged is the importance of their personal, almost intimate relationship with the actors, whose “truth” is sought. The auteurs I interviewed are keen and very proud of “discovering” new actors. In some cases, the film itself is born thanks to the director’s direct knowledge and friendship with a series of actors; for example, Valerio Mastandrea does not need to be auditioned because he always “plays himself.” In other cases, the film is developed on the basis of a series of castings after writing the screenplay.

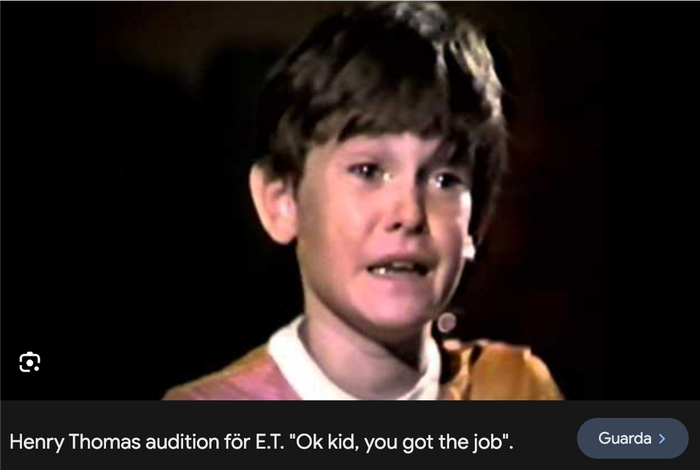

The audition is a source of discomfort for the auteurs I interviewed, as if that was not the place where the effectiveness of an artistic choice can emerge: “That something that makes you say ‘there he/she is!’.” Therefore, for important roles, the human relationship is fundamental, spending time with the actor talking about the film, the character and “other things, seeing how he moves, grasping things about him not only as an actor.” What emerged is the difficulty of establishing a boundary between fiction and reality and the vision of the film as a “piece of life,” a “home” with actors as temporary guests.

The auteurs’ intolerance is aimed at “the grids of faces that are all the same proposed by casting and agencies,” and by the deeply felt need to be surprised by reality, to make "reality" happen, be surprised by a “new” face, outside of the dominant media conformism. In front of the camera, what is important is that the actor surprises himself while surprising the director who sometimes seems to seek the actor’s transparency, the moment in which the actor disappears to reveal something unrepeatable.

In the past, before casting directors existed, in order to find the film protagonists, productions resorted to local casting, with the initial refusal of an audition on part. The search for the “right” actor meant that with the limited means available, productions had to call agents in Rome and explain to them what the director wanted. At this point, the same proposals always arrived from the agencies with the purebred horses and the new ones to “push.” That’s why it was considered very important to see every single actor the agencies represented, and if nothing came out, looking elsewhere, everywhere.

In conclusion, it seems interesting to point out Italian casting directors’ awareness of the differentiation between Italian acting schools’ methods and the complaint, from a few of them, about the lack of interaction between film directors and film actors during their training, in addition to the fact that there is almost no training on casting and self-tape making. In conclusion, between actors who play themselves and actors “taken from the street,” according to my research, misquoting the title of our conference, it is possible to state that according to the main rhetoric actors are “born”, not made.

"Cinema is made of faces"

Performers' Digital Databases

The "Quid"